(This is a piece that was intended for print but put on hold when COVID hit. We decided not to wait any longer to share it with you.)

It’s a sunny day as I gingerly descend from Bloomfield into Lawrenceville after a quick winter freeze. I’m visiting atiya jones’s art studio in the Lawrenceville Radiant Hall location. Born in New York, jones moved to Pittsburgh in 2016 in part to do a residency at Bunker Projects in Garfield. She works in multiple mediums, producing intricate drawings that weave line and shape into itself, photographs, and client work.

Our discussion centers around the use of the drawn line and how the clustering of these “wild lines” relates to something as omnipresent as gentrification and the need for visibility in an inequitable world.

David Bernabo: How did your drawing style emerge?

atiya jones: The style emerged from what the kids are calling “imposter syndrome.” I was painting a lot. I use paint, but I’m not a painter. I was feeling really insecure about the work. It wasn’t work that felt genuine to things that I had to say at the time, but it was what I was capable of producing.

atiya jones: The style emerged from what the kids are calling “imposter syndrome.” I was painting a lot. I use paint, but I’m not a painter. I was feeling really insecure about the work. It wasn’t work that felt genuine to things that I had to say at the time, but it was what I was capable of producing.

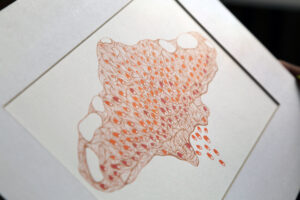

So, I thought I should just sit down and draw. I won’t care what comes out. The first thing that I drew was a blue pod with red coming out of it. I looked at it and it reminds me so much of my friend and the symbiotic relationship she has with her brother. So, I immediately saw something in this work. Over 30 days [of drawing], the line work shifted dramatically from this little thing to things that had stories to me.

The themes didn’t start to kick in until I saw the way what I was observing in life was translating into the work. I call them “wild lines.” I consider the wild lines to be a language. It’s my lexicon.

DB: Is it fair to say that each line is responsive to the lines that are on the page at that point in time?

aj: Everything is responding to what happened before. But that starts to feel really intense. I have to move to a different space on the page, because [the drawing] will get clustered and hyper-focused. Like with mental health, there are reminders that oh, you are way too zeroed in on this one aspect of this drawing or this aspect of your life. Remember to pull back, observe the scene, actually see what’s happening. And that’s one of the places where gentrification pops into mind.

aj: Everything is responding to what happened before. But that starts to feel really intense. I have to move to a different space on the page, because [the drawing] will get clustered and hyper-focused. Like with mental health, there are reminders that oh, you are way too zeroed in on this one aspect of this drawing or this aspect of your life. Remember to pull back, observe the scene, actually see what’s happening. And that’s one of the places where gentrification pops into mind.

Gentrification ties into everything. We’re human beings living in 2019. If you can afford your rent, you probably displaced someone who couldn’t. Having spent most of my life in New York and getting in the hampster wheel of working and paying rent, and thinking about the point where I would never own anything in New York–I would never get to a place where I am secure and I have made it. I didn’t feel like a future would be possible for me there. Think about the history behind that mindset–people of color not being legally allowed to own homes in certain area. America’s history of redlining is an aspect of racism that we do not talk about very much in regards to business and property ownership. All of those things have affected the mindset of black Americans. I’m still on the trickle-down of that.

DB: And practices like redlining are continually updated in new policies.

aj: Absolutely, that roster is still rolling. What I have absorbed in Pittsburgh in regards to blackness and black American culture and collective self-worth is that the order of [identity] is different in New York. In New York, it’s where you live, what you do, and then other echelons of existence. In Pittsburgh, it’s very racially defined, then where you live, and then the other things. That affects the mindsets of folks.

aj: Absolutely, that roster is still rolling. What I have absorbed in Pittsburgh in regards to blackness and black American culture and collective self-worth is that the order of [identity] is different in New York. In New York, it’s where you live, what you do, and then other echelons of existence. In Pittsburgh, it’s very racially defined, then where you live, and then the other things. That affects the mindsets of folks.

As new businesses open, you have people from black communities saying, oh, this space is not for me. This is a two-sided problem because you have a group of people that have been told, literally, that spaces are not for them through redlining and segregation. And then you have business owners that do not understand how to make spaces inclusive.

But an integral part of my artistic story arc–I was doing a live installation, a live mural painting at a block party in Brooklyn. This young girl came over to me and asked if I was an artist. She was like I’ve never met an artist before. I’ve never seen anyone make art before. That’s a thing that I take for granted. I came from an artistic family. I went to pretty good schools and we would take trips to the museum. So, the fact that I was doing what I was already doing, but just doing it outside could impact the lives of people. Also, being a black, queer woman, every opportunity that I get to be publicly facing . . . I, generally, will say yes to things. This is important, take my picture, put me in things. People need to see me. White people need to see me and young black people need to see. Shit, old black people need to see me. It’s important for visibility. That’s a huge part of gentrification–the erasure of history.

DB: Your client work has led to having your work in the Tryp Hotel and the new Beauty Shoppe Terminal Building. How do you balance the various aspects of your practice: drawing, photography, and client work?

aj: I started taking photography classes in seventh grade. The darkroom was a very active part of my life. I slowed down on picture taking in 2011 when it got harder to find places to process [film]. But I started shooting again two years ago. I found my old negatives and remembered that this is the thing that I’ve been doing the longest. It’s been really fun to share that work. I’m not sure what I want to doing with it. Making art, in general, brings me joy. But photography purely brings me joy as there is no capital attachment to it.

aj: I started taking photography classes in seventh grade. The darkroom was a very active part of my life. I slowed down on picture taking in 2011 when it got harder to find places to process [film]. But I started shooting again two years ago. I found my old negatives and remembered that this is the thing that I’ve been doing the longest. It’s been really fun to share that work. I’m not sure what I want to doing with it. Making art, in general, brings me joy. But photography purely brings me joy as there is no capital attachment to it.

The linework is like having a conversation. The linework and the client work are deeply entangled at this point. It has become my trademark. In regards to balance, I might have to get back to you on that. I don’t have any.

DB: Do you have a job outside of art?

aj: I still have a part time job. In thinking about work, when I moved to Pittsburgh, I started working at Ace Hotel. I was familiar with Ace Hotel from New York, so brand alignment worked for me. I worked at the front desk and later became the Human Resources director. There were changes that I wanted to see happen. Being able to foster that space for the time that I did, meeting community members and people that access that space as a safe haven, whether social or for work, that’s one of the aspects of how communities build. Of course, it is a problematic establishment in regards to gentrification. But what do you do with that? Because someone is going to move into the space. Now that we’re here, it’s a matter of what do you do with your seat at the table, for me at least. I think that’s an aspect of gentrifying cities that we don’t talk about enough. There’s a lot of protests, but it’s a losing battle. Your city is changing. To say that you don’t want the Starbucks to move in–like, yes–but the thing is is that the Starbucks is probably going to move in. Can you get them to do local programming? If these places are going to get in, what are their responsibilities to your community? Those are the conversations that I’m more interested in.

I’m very thankful that I get to make the the work that I want to make, but it’s such a small stamp in my mind. I love this aspect of marking territory and saying this is a space that I enjoy or here’s a group of people that have supported me and I want to respect their efforts with the thing that I have to offer. So, I try to be selective with the clients that I work with. I work with businesses that I genuinely love.

One of the first spaces that I worked with in Pittsburgh was Crown Barbershop on Penn Avenue. My good friend owns that space. I wanted to offer artwork to a community that felt like they couldn’t go into the room. That’s one of the things that I heard a lot when I moved here. Like, that’s not for me, that place is not for black people. So, how I process that is what can I give you while you are outside. So, that’s where these window installations started, and the installations have turned into its own monster. Like everyone wants art in the windows. Sick! Let’s do it.

At the Tryp Hotel, through Casey Droege, they asked me to design the chalkboards in all the rooms. Once that was done, they asked me to activate the space outside the Brickshop. One of my favorite things about that mural, when you are walking by, you can see the mural through the glass. So, it still sits within the realms of what I want, morally, for my work. I want the work to be accessible. It’s still visible if you know to look. Which is much of life–if you know to look, you’ll see magic.

My vision with art is that art is everywhere. Brands need it to survive. Even a brand that does not use art, they still use a type face. Everything is a decision in every product. So, in thinking about marginalized peoples, often craftspersons and artists are at the bottom of this list, but our work is being exploited for all needs. So, I take corporate gigs, because someone will and why not me. I’ve seen a lot of white guys take these gigs. I had a friend that’s a very profound, very successful muralist and we were talking–this was in 2014–and he said you know if you want to make money, you need to care less. This is the mindset. That’s like the male mediocrity thing that we’re seeing all the time everywhere. Do I jump on board with that mindset? I won’t do it. I can’t. But understanding that that is out there makes me work so much harder. If people like that are getting hired for things, there has to be space for people that are passionate and putting their emotional and mental exertion into their work.

My vision with art is that art is everywhere. Brands need it to survive. Even a brand that does not use art, they still use a type face. Everything is a decision in every product. So, in thinking about marginalized peoples, often craftspersons and artists are at the bottom of this list, but our work is being exploited for all needs. So, I take corporate gigs, because someone will and why not me. I’ve seen a lot of white guys take these gigs. I had a friend that’s a very profound, very successful muralist and we were talking–this was in 2014–and he said you know if you want to make money, you need to care less. This is the mindset. That’s like the male mediocrity thing that we’re seeing all the time everywhere. Do I jump on board with that mindset? I won’t do it. I can’t. But understanding that that is out there makes me work so much harder. If people like that are getting hired for things, there has to be space for people that are passionate and putting their emotional and mental exertion into their work.