OVER THE LAST CENTURY, Pittsburgh authors have provided major signposts along the visionary road map toward America’s Hopeful Environmental Future.

The first was Haniel Long, esteemed English Department chair during the 1920s at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), who wrote a futuristic 1,100-word short story for the June 20, 1923 issue of The Nation.

“How Pittsburgh Returned to the Jungle” was a sly Swiftian satire that traced the implausible series of unintended events stemming from an obscure civic ordinance mandating every single window in the city be equipped with a flower box bearing live plants. The ensuing floral profusion quickly transformed industrial Pittsburgh into a smog-free, globally-acclaimed utopia of scenic beauty and abundant prosperity.

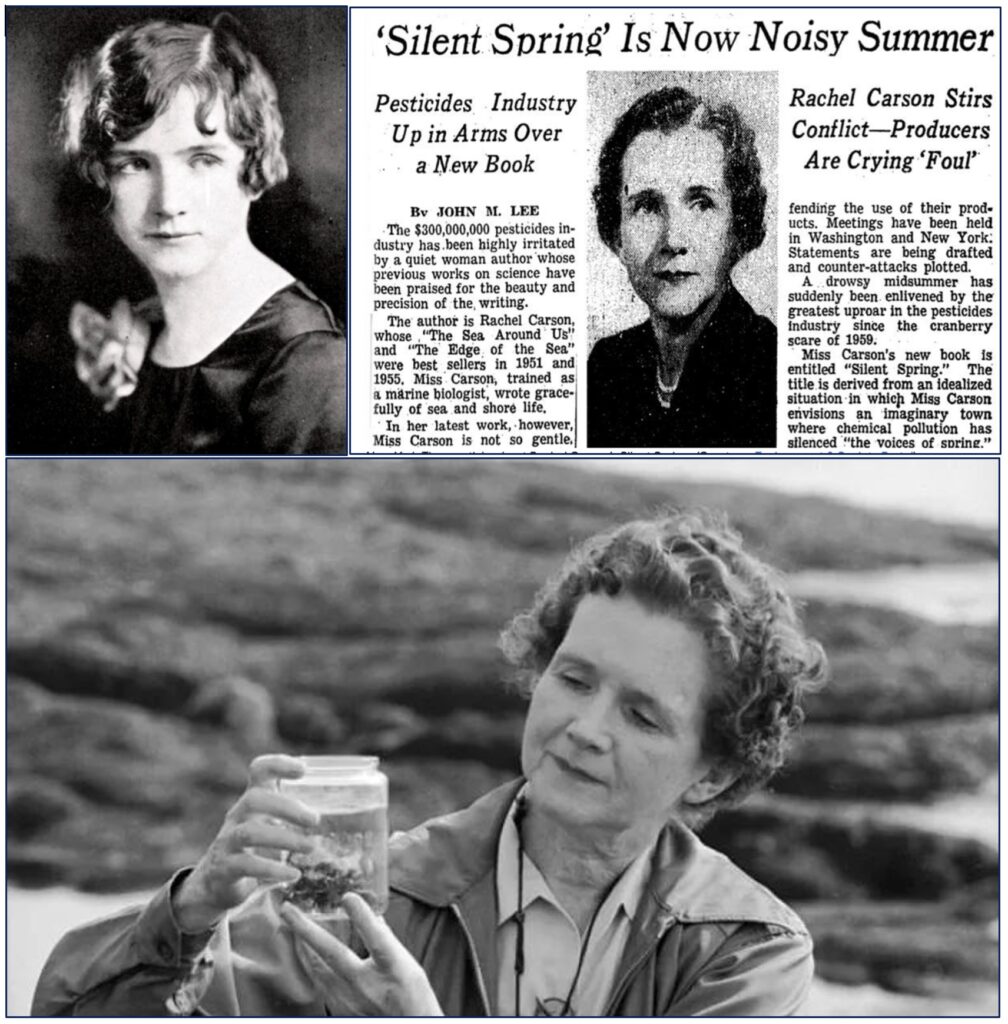

In the 1960s, marine biologist and Springdale native Rachel Carson shared the natural wonder of her Allegheny River childhood in best-selling books like Silent Spring and The Sea Around Us, bringing the irrefutable weight of science to expose the damage chemical pollution wreaks on soil, air, water and living beings around the world.

Today, the prophecy of Long and scholarship of Carson have found compelling new expression in a just-published memoir on environmental activism by Chatham University professor Patricia DeMarco, Ph.D.

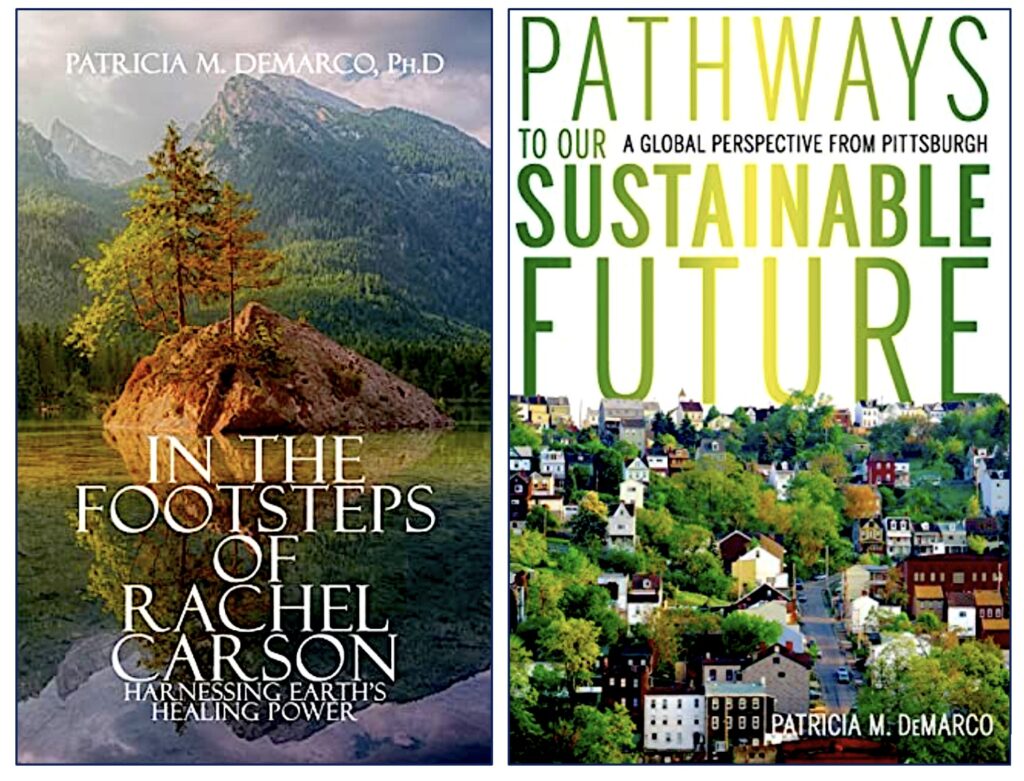

In the Footsteps of Rachel Carson: Harnessing Earth’s Healing Power (Urban Press) takes up where DeMarco’s 2017 Pathways to Our Sustainable Future: A Global Perspective from Pittsburgh (University of Pittsburgh Press) left off, addressing the question that sustainability advocates ponder on Earth Day and every day through the year — what can individuals do that will truly make a difference in protecting our environment?

In the Footsteps of Rachel Carson: Harnessing Earth’s Healing Power (Urban Press) takes up where DeMarco’s 2017 Pathways to Our Sustainable Future: A Global Perspective from Pittsburgh (University of Pittsburgh Press) left off, addressing the question that sustainability advocates ponder on Earth Day and every day through the year — what can individuals do that will truly make a difference in protecting our environment?

DeMarco spent her formative years in Mount Washington with Italian immigrant grandparents, whose passion for gardening and neighborhood activism shaped her eventual life’s work in biodiversity and social justice. After earning B.S. and Ph.D. degrees in Biology from the University of Pittsburgh augmented with post-grad biochemical genetics research at Yale University and Boston University School of Medicine, she pursued a 30-year energy and environmental administration career in Alaska, Connecticut and Pennsylvania.

In 2011 DeMarco was named Director of the Rachel Carson Institute at Chatham University, following a five-year term as Executive Director of the Rachel Carson Homestead Association. She currently serves as Vice President of Forest Hills Borough Council and participates in a dozen or more public lectures and panels during the year, addressing innovative practices in clean energy, environmental protection and green jobs development.

Three years ago she was among the founders of ReImagine Appalachia, a four-state consortium that drew 15,000 citizens to nearly 50 live and virtual Sustainable Justice Forums across Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Kentucky. The resulting recommendations produced a series of environment-friendly, community-reviving economic development policies that made up the core of the landmark Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by Congress in 2021.

In the Footsteps of Rachel Carson: Harnessing Earth’s Healing Power offers an illuminating look at DeMarco’s half-century of advocacy and research. It’s also an intensely personal memoir revealing how four bouts with cancer strenthened her already deep connection with the healing powers of nature.

“Rachel Carson has been my beacon and inspiration,” she notes. “I share my own journey out of the conviction that to have healthy people, we need a healthy world.”

* * *

LOCALpittsburgh: How did the first time you read Rachel Carson reach you on a deep personal level?

Patricia DeMarco: I first encountered her writing at the age of 12 as I was returning to Pittsburgh from a two-year stay in Brazil with my family. We were on a steam ocean liner, where a copy of The Sea Around Us was on the coffee table in the lounge. I was immediately captivated by her descriptions of what was under and around the boat I was traveling on through strange waters and endless waves in all directions. Her writing brought that apparently unremarkable seascape to life, and I was captured by imagining the water world below me. A few years later for a high school graduation present, I received a copy of Silent Spring. She became my hero and role model.

As a woman scientist and writer, her power came from the way she merged facts and science with passionate, descriptive writing. With Silent Spring, she turned a book about chemicals and their effect on living systems into a dramatic journey of the imagination. She gave credibility and force to the process of asking questions, seeking answers and using information for persuasion. I still turn to her writing when I seek inspiration or comfort in this journey of advocacy for the Earth.

LOCALpittsburgh: From when you first fully understood the Earth’s environmental fragility and now up to the present, what do you think has improved, or gotten worse?

DeMarco: When I was working for the State of Connecticut in the late 1970s as Executive Director of the Power Facilities Evaluation Council and the governor’s liaison to the Connecticut Energy Advisory Board. In the aftermath of Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, we were trying to see how to address low-level and high-level nuclear waste from the four nuclear power plants operating in Connecticut. It was very clear to me that our policies and programs were totally inadequate to manage nuclear waste effectively on any level.

Over the last 50 years, Americans have increased the amount and toxicity of the garbage we produce per capita. I think the pollution of land and the proliferation of practices that cause irreversible damage, as from nuclear waste and non-biodegradable plastics, has become much worse. Plastic pollution is now a global threat to biodiversity, carrying endocrine-disrupting synthetic materials to the ends of the earth and incorporating contaminants into the food chain from the micro level on up to humans. I see few realistic remedies to these issues without a major change in laws controlling the production and recovery of synthetic materials.

LOCALpittsburgh: But you believe there has been some improvement in our environmental condition?

DeMarco: Due to the Clean Air Act of 1970, air quality has improved significantly through the actions of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency formed in the wake of the first Earth Day. Though there are more pollution reductions needed — and many also associated with controlling greenhouse gas emissions at the same time — there are few places in America where the air is suffocatingly poisonous all of the time. With water pollution abatement from the Clean Water Act of 1972, water contamination from industrial discharges, sewage treatment plants and agricultural runoff into navigable waters was significantly reduced. The Safe Drinking Water Act in 1974 addressed the public health aspects of water pollution and established standards for public water supply. For most of the U.S. these measures have been helpful.

LOCALpittsburgh: When you teach about the environment, what do you want your students to grasp?

DeMarco: I hope all of my students come away from my class with a sense of empowerment to move from despair to action. However, we are in a time of great transformative change, which is both frightening and exciting. Our civilization is facing a triple existential threat of climate warming, global pollution and global loss of biodiversity. It is a time to recognize that the ways of the past cannot sustain our civilization for the future.

LOCALpittsburgh: Once they recognize this, what next?

DeMarco: We must recognize that the laws of Nature are not negotiable. Humans must adjust our laws and our way of life to be in harmony with the laws of Nature, if we are to survive and thrive. We have to recognize that the challenge is not one of technology but of ethics and moral responsibility to the children of our time and for the future.

The solutions to these existential crises are known, proven and available. Implementing them on a global scale is fraught with inequities, blocked by vested interests in fossil industries, hampered by fear of an unknown and unfamiliar future.

And very importantly, each person can act as an agent of change. The pathways to a better future are at hand and ready for us to take.

LOCALpittsburgh: The Pittsburgh area has a large number of civic and nonprofit groups working to aid the environment. Is there a way they might work together more effectively?

DeMarco: Environmental groups do work together when there is a uniting cause, but usually each has a separate and specific piece of the issue. The issues are numerous, yet often they overlap. We need better leadership to draw these dedicated and wonderful organizations into harmony with a single unifying vision.

Additionally, it is not only environmental groups who need to be at the table but also social justice and faith communities, transportation and housing advocates. For example, this past April, Lancaster County held an Earth Day Climate Summit with 5,000 attendees. It involved government entities, local organizations, universities and community groups with cultural events to tie them together. Can we do that here in Allegheny County?

LOCALpittsburgh: Do you think if we could straighten out our environmental mistakes, it would make us better people? A correlation, perhaps, with how we steward the earth and treat other humans.

DeMarco: We cannot have healthy people in a sick environment. The Earth has the capacity to heal, but we must help by preserving the natural systems that provide our life support.

When people come to understand the interconnectedness of living systems — the great web of life of which humans are only one part — it becomes more clear that we can improve the quality of life for everyone if we improve the conditions in which they are living.

On a very basic personal level, it is easier to be friendly to neighbors in a community that is beautiful and green and has shared green spaces than in a blighted concrete-walled cityscape with nothing alive in it. Just placing plantings at sidewalk edges or growing a community garden helps center community and generate shared achievement.

It may be idealistic to think that restoring green spaces and gardens can restore a sense of mutual respect and dignity for people. Care for all of creation includes care for the people as well as the creatures.

LOCALpittsburgh: What can the ordinary citizen do to get laws passed that protect our environment?

DeMarco: Three things. First, elect people with a true commitment to a quality environment for everyone. Having clean air and water should not be determined by your zip code. We need elected officials at all levels who place clean air and water and preventing pollution at the top of the agenda, as a basic criterion for decision.

Second, check to see who funds a candidate. If the candidate is taking money from polluters, chances are good that they will protect those interests when they are in office.

Third, when there are hearings or public meetings on environmental issues, show up and speak up. Public comment is required for many laws and regulations as they are being considered. The voices of people affected by air and water pollution and damaged lands must speak up and demand accountability. # # #