THIS PAST JULY 24 in Wilkinsburg, Forever Free — a newly-sculpted statue of Abraham Lincoln, America’s 16th president — was ceremonially presented to an enthusiastic audience of a hundred or so history buffs gathered on a small concrete-and-grass traffic apron bounded by Penn Avenue and Dell Way overlooking the intersection of Ardmore Boulevard and Ross Avenue.

WTAE-TV news anchor Andrew Stockey served as the event’s master of ceremonies, introducing Wilkinsburg Council president Pamela Macklin and historical commentators Paul Guggenheimer, Jonathan Ray and David Wiegers, along with sanctifications from Fr. Chuck Esposito and Rev. Thomas Mitchell, a resounding Pledge of Allegiance led by Girl Scout Troop 52326, a brief expression of gratitude from Lincoln re-enactor Kevin Santillo and standout musical contributions from Chantal Braziel, Tania Grubbs, Hill Jordan, Mimi Jong, Keith Cochran and Melissa Alliston.

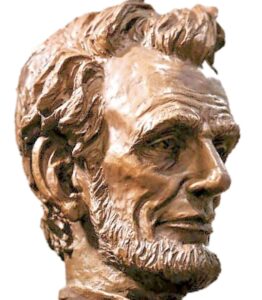

Aided by Wilkinsburg Historical Society president Anne Elise Morris, the statue’s sculptor, Susan Wagner of Pittsburgh, carefully removed the bright red shroud to reveal a three-dimensional, life-size vision of one of American Civic Mythology’s most esteemed figures.

From empires to republics, in sprawling capitals and remote villages, monumental sculpture has for centuries functioned as a medium societies use to tell stories of heroic individuals and memorable events in their history.

Forever Free is squarely in the classical Heroic Sculpture tradition, but Wagner’s interpretation aims to be more accessible. It presents Lincoln as an ordinary man in a moment anyone can relate to — collecting his thoughts as he gets ready to give a speech. In this case, a speech that will forever change the course of U.S. and world history — Proclamation 95, an executive order better known as The Emancipation Proclamation.

This unapologetic ordinariness has always been the most compelling aspect of Lincoln’s enduring appeal. He was One of Us. We remember his jokes, his humility, his ceaseless quest to see the better angels of our nature … and help us see them, too.

To contemporary Americans, Lincoln still occupies an elevated status signifying wisdom, tolerance and the ongoing duty of government to bring about social justice. The day’s speakers repeatedly expressed his relevance for our time as a moral beacon and resolute guide through the troubling political waters of the 2020s and, perhaps, beyond.

There was also a sentiment among borough residents that replacing the original Lincoln statue, first mounted on the site in 1916, represents another small but important ingredient aiding the long-brewing Wilkinsburg economic revival.

Or, as The Rail Splitter himself once said: “Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.”

Susan Wagner has been sculpting professionally for three decades, and her life-size renditions of Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, Bill Mazeroski, Jackie Robinson and Dr. Thomas Starzl have received international acclaim. She has created singular works for the Allegheny County Law Enforcement Officers Memorial, Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium, UPMC Passavant Hospital, National Baseball Hall of Fame, 14th Quartermaster Base in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, and for venues outside the continental U.S. (the Vatican, Canada, Brunei, Puerto Rico).

Recently, Ms. Wagner took a few moments to talk about her sculpting process.

* * * * *

LOCALpittsburgh: Making any kind of large-scale sculpture, especially one that will be seen by thousands of people each week, is certainly an involved process. What is the first thought that comes into your mind after you’ve received the commission to create the piece?

Susan Wagner: Fear.

LOCALpittsburgh: Fear?

Susan Wagner: Yes, and you can quote that.

LOCALpittsburgh: We will!

Susan Wagner: Seriously, it’s something you use to stimulate and steady you as you embark on the journey. There are many Lincoln statues all over, and they’ve been done so well. At first I thought, “How can I live up to that legacy?” But I work every single day until it’s done. I don’t take days off, I get up every morning and work until it’s done. That’s what it takes.

LOCALpittsburgh: What input do you get from the people who commission the work?

Susan Wagner: At the very outset, I meet the client and let them know what to expect. I explain how long it takes, all the steps in the process. For instance, they have to understand creating a life-size sculpture will take several months. I break down the costs for each part of the process — materials, hiring a welder, transportation to and from the casting site and so on. They have to approve the clay before it’s sent to the foundry. They have to approve the finished form of the sculpture, because once it gets to the foundry, nothing will change. This way the client knows exactly what to expect.

LOCALpittsburgh: Are the pieces also site-specific?

Susan Wagner: Absolutely. I visit the site where the statue will be placed. I have to sculpt something to fit that specific space. I see what kind of foot traffic there is, how it flows. Then I do a lot of research on the subject — books, articles, all the photographs I can find. And photographs from every angle, because the sculpture is usually going to be three-dimensional and viewable from 360 degrees.

LOCALpittsburgh: Does having the figure be life-size help people relate to it?

Susan Wagner: Yes, and it’s also dependent upon the space. I couldn’t make a 30-foot high Abraham Lincoln for the site in Wilkinsburg. It would be too much.

LOCALpittsburgh: After this preparation, how do you come up with your own idea to portray the character or event?

Susan Wagner: With Lincoln, I had a very, very small physical space where the placement would be. I could not make anything in motion. I had to stick to him standing. And, opposed to what I just said about three-dimensionality, it was clear that most viewers for this piece are only going to see the statue one way — as they drive by. I did manage to get some movement … his head is turned a little.

LOCALpittsburgh: But, unlike the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. where he’s sitting and staring straight ahead, your sculpture has a lot of implied movement. He’s just standing, yes, but you get a strong sense with the scroll in his hand, the other hand holding his coat lapel, his left foot turned out, the set and wrinkles of his clothing — all that makes it seem as if he’s moving or about to.

Susan Wagner: As I do my initial research, I try to convey the spirit of the person … what makes them unique. And if the person is living, I try to interview them and observe them as they speak and move. With Dr. Starzl, the renowned University of Pittsburgh transplant surgeon, I was able to meet him several times. Even if I sculpt an animal, I try to imagine what it’s like being them. What they’ve lived through, what they go through on a daily basis. I make my hands the conduit for the spirit to move into clay.

LOCALpittsburgh: How did that work for Lincoln?

Susan Wagner: I had him posing as he’s just about to give the Emancipation Proclamation speech. He’s thinking deeply, because he knows this speech is going to be very powerful, changing the course of the war, the country, even the world. That was the moment I felt the spirit was strongest.

LOCALpittsburgh: So with your sculpting, you imagine a precise moment in time?

Susan Wagner: Exactly. And then the individual’s intent. I always try to get a lot of emotion in the face and the body. With Dr. Starzl, the piece shows him sitting and contemplating an upcoming surgery he’s due to perform. He was very intelligent, very sensitive, very socially-conscious. That was the emotional mix, the personality I tried to get into the clay.

LOCALpittsburgh: Actual personality traits?

Susan Wagner: Yes. I just finished a bust of an 89-year-old woman. I got to meet her. We only spoke just briefly, but I think intuition goes a long way for an artist. I perceived a very genteel regalness as we spoke, and that was one of the elements I tried to capture.

LOCALpittsburgh: Once you have the initial clay sculpture finished, what happens?

Susan Wagner: I have the client come and look. Once I get their approval, the foundry comes in. You must have a good foundry. It’s like a good marriage. There must be constant communication. We have to work as a team.

LOCALpittsburgh: What foundry did you use for Lincoln?

Susan Wagner: Studio Foundry in Cleveland, Ohio. They make a mold of the sculpture, and each sculpture has its own challenges and requires its own way to be handled and transported. I have had several pieces ruined at a foundry, so care always has to be taken.

LOCALpittsburgh: What happens after your original arrives at the foundry?

Susan Wagner: You’re essentially making a duplicate sculpture. A rubber mold is applied to the clay, it’s a chemical composition. Then a thick layer of plastic is applied, all of it done in pieces. When that’s cured, the clay is no longer needed and is cut into pieces and removed. The mother mold has wax poured into it, as if you’re making a candle with different layers. The wax has to be a certain thickness and cover every bit of the statue. Then the positive wax is dipped in liquid ceramic, and many laters are built up. That is cured and put in a kiln. At the same time, the wax melts away back into liquid.

LOCALpittsburgh: Pretty intricate!

Susan Wagner: It’s called the “lost-wax method”, and it goes back thousands of years to India and the Middle East. The cured ceramic is very hard, like a dinner plate. That’s when it’s safe to pour in the molten bronze. The bronze cools, and the ceramic mold is chipped away. Each piece of the sculpture is complete and ready to be assembled … a head here, a torso there, hands, arms, all those pieces are welded together. A patina is applied, and that’s where the color comes. Raw bronze is the color of champagne, and the patina adds life and protects the bronze. For further protection, wax is applied onto the patina.

LOCALpittsburgh: When you started out in the art field, what was it about the idiom of sculpture that piqued your interest? What made you think it would be a way for you to express your artistry?

Susan Wagner: Faces fascinate me. Any human figure I see fascinates me. Ever since I was little, I’ve been amazed at how everything works together, how muscles work together to create movement. I would sketch my little friends. I dug clay out of the earth and would take it home and play with it. Sculpt with it.

LOCALpittsburgh: What was your first public sculpture?

Susan Wagner: The 14th Quartermaster Detachment Memorial in Greensburg was my first lifesize figure, and that was in 1992. It commemorated the 13 men and women killed in their barracks by an Iraqi missile during Operation Desert Storm. I had been sculpting for corporations for 10 years, bas-relief work. I took it for casting at Polich Tallix Fine Art Foundry in upstate New York, just outside Newburgh. It was the first time I’d met other sculptors. Really a whole new world for me.

LOCALpittsburgh: With the advent of photography and then film and video, the purely instructive function of sculpture has become less essential. You’d probably agree, though, that even today public statues can evoke very strong emotional responses.

Susan Wagner: When I was at the foundry in New York sculpting the Roberto Clemente statue, one of the workers was from Puerto Rico. One day, he grabbed my hands, kissed the top of my hands and said, “Bless your hands and thank you for bringing him back to us.” I will never forget that. I get chills telling you now. That’s the way a sculpture can tell a story in our time. You can see pictures of the great athlete Roberto Clemente in books, you can watch him in videos, but there’s still a detachment. With sculpture, you can go and touch him. It is bringing him back. With Dr. Starzl’s sculpture I have him sitting on a park bench. An actual bench. His widow visits every day and sits next to him.

LOCALpittsburgh: You can do that with sculpture.

Susan Wagner: You can do that with sculpture — if you can get the right kind of emotional connection.