LAST SUMMER painter/architect Cory Bonnet moved his New Vision Studio into 10,000 square feet of space spread throughout the Energy Innovation Center at 1435 Bedford Avenue in the former Clifford B. Connelley Vocational High School, just up the hill from PPG Paints Arena.

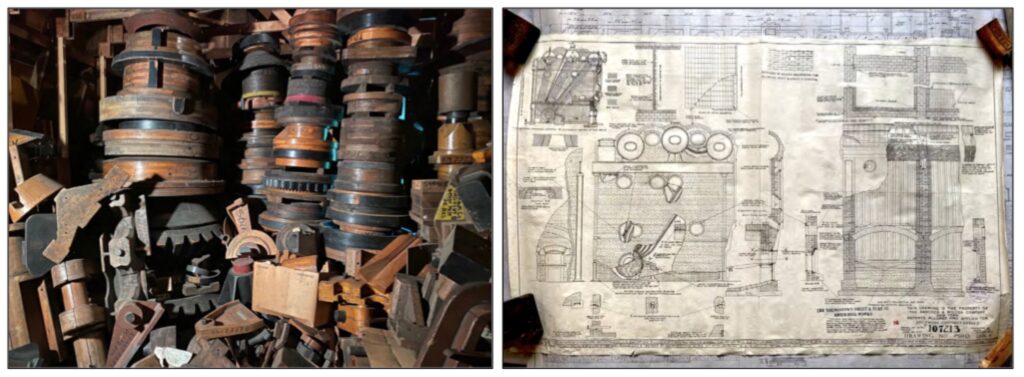

The footage filled up fast when he and New Castle art gallery owner Chip Barletto brought in 10 box-truck loads of approximately 6,000 wood patterns, blueprints and other foundry tool-making artifacts used in the region’s steelmaking industry during the 1890s-early 1900s.

Rescued from the Youngstown Sheet & Tube’s Campbell and Brier Hill Works that closed in the late 1970s, the artifacts represent the design DNA American factories utilized to manufacture the 20th Century.

Thanks to Bonnet and Barletto, they’re having a 21st-century renaissance.

This Monday, May 16, the entire collection assembled so far — Patterns of Meaning: Historic Steel Mill Artifacts, Contemporary Oil Painting — will be open to the public from 6-10 p.m.

Attendees must register on Eventbrite.

The exhibit takes place in conjunction with AISTech 2022, the annual conference of the Association for Iron and Steel Technology occurring May 16-18 at David L. Lawrence Convention Center. Bonnet will have a booth at the conference with collection samples and information, and conference attendees arriving via Pittsburgh International Airport will be greeted by an installation featuring several from the Patterns of Meaning trove.

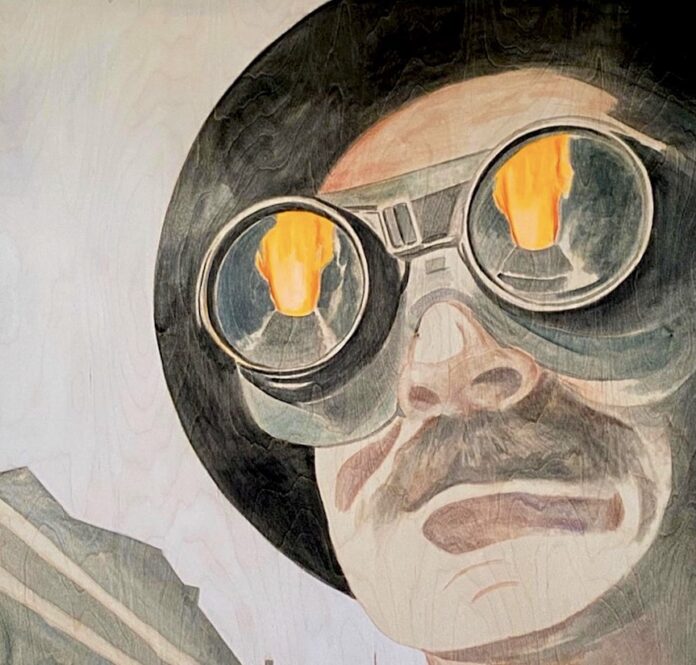

Cory Bonnet has been painting Pittsburgh history for two decades, from landscapes and historic sites to neighborhood murals like the one at Firemen’s Park on Shiloh Street in Mount Washington. Early on he incorporated reclaimed materials into his work and earned certification from the U.S. Green Building Council as a LEED Accredited Professional in sustainable architecture and planning. His heritage-themed artwork was recognized with a 2017 Preservationist of the Year award from Young Preservationists Association of Pittsburgh.

LOCALpittsburgh caught up with the busy artist as he prepared for the latest Patterns of Meaning exhibit.

Q. In a nutshell, what’s the importance of having a collection of 6,000 century-old steel foundry artifacts?

A. The patterns and artwork are touchstones telling the story of the workers and innovators who built the foundations of our modern world. And it was accomplished with a fraction of the technology we enjoy today. To a contemporary artist or designer, the craftmanship in even one of these pieces is mind-blowing. Most of the patterns were destroyed when the mills closed, but the collection we have from this one mill is unparalled.

Q. How did you find it?

A. A few years back, a fellow from New Castle named Chip Barletto saw my posts on Facebook and contacted me. “Hey, I’m a scrap guy, I work in scrap metal, my dad was a heavy machine operator, I’ve been around steel all my life, I’d love to see your art.” Chip came to my studio in the Strip District, loved what I was doing with salvaged material, and we stayed in touch. One day I got a text from him that said, “Do you want this?” It was a photo of a 9-foot tall, 15-foot wide wood pattern used for a giant steel plant ladle. I said, “Yeh, I’ll take it,” and I’d figure out what to do with it.

I moved into the Energy Innovation Center in March, 2020 — just as the pandemic hit — and then Chip called and said he’d located more of these patterns, and we should drive up to the barn in Ohio where they were stored.

Q. You were surprised by what you found in the barn?

A. Astounded. Floor-to-ceiling pristine sand-casting patterns for steelmaking tools. Gears, wheels, piles of railcar wheels, crankshafts. In the basement of the home, there was a whole wall of rolled-up blueprints, thousands of them that corresponded to all the patterns we found in the barn.

Q. This was a rare find.

A. The only reason this collection had stayed together was because Gene Koch, the man who got these from the steel plant, didn’t break it apart. And when he passed away, his wife Evelyn never broke it apart. The more Chip and I saw, we realized how beautiful and unique these pieces were. We wanted to come up with a way to honor the craftsmanship and heritage of the patterns and the workers who created them.

Q. So you get back to Pittsburgh, you’ve unloaded the 10 trucks and …

A. And Chip and I said, “How do we preserve it and exhibit it?” First we inventoried and catalogued it, which is an ongoing process. We’ve had events where people are invited to come by and see what we have and if they can use it in a creative or teaching way.

Q. This seems like a gold mine for artists looking for materials.

A. We want to get it back into the world in forms that are artful and useful. I’ve talked to artists in glass and ceramics and steel about casting new products and objects from these existing molds. For example, you could do porcelain casts from some of the smaller pieces and those can be combined with things to make chandeliers, light fixtures. You can do large pours in glass to create an absolutely magnificent table or some kind of original decorative piece never seen before. There are so many possible uses — sculptural works, architectual elements, fittings for building lobbies.

Q. A new style of contemporary industrial art fashioned from actual industrial art forms.

A. It’s basic adaptive reuse. We’re hoping to put together a Patterns of Meaning exhibit that can travel to institutions, museums, galleries and show how adapting materials you already have can inspire new ways of solving a problem in art or in business.

Q. And this is all getting put together in what was Pittsburgh’s biggest trade school for over 70 years.

A. Yes, the Connelley Technical Insitute opened in 1930 and closed in 2004. It was considered one of the premier trade schools in the country. And today there is a huge shortage of workers in trade professions across the U.S. Why not use the foundry materials to start an arts apprenticeship program in carpentry and woodcraft? Welders, metalworkers can learn the basics here, so when they get into a formal trade school, they have a starting point and realize how much you can get from pursuing a creative profession. The Energy Innovation Center already has training where they’re setting people up for good-paying jobs in the trades. Our materials can certainly play a role.

Q. What were your first art experiences?

A. My earliest memories are coloring books. Coloring them all the time as a child. When I was four, I broke my hand. I was left-handed, but when that hand got bandaged and I tried to color with it, I was all outside the lines. Eventually, I tried with my right hand, and I kept at this Donald Duck coloring book for two weeks straight until I could get into the lines. That’s my earliest memory of doing art. I knew even then I would be doing art as an adult, but I had no idea how it would all come together.

Q. How did your formal art training mix with your passion for sustainability?

A. I earned a BFA in Drawing and a Minor in Art History from Edinboro University of Pennsylvania. But I was always aware of the factories in town, what went on in them and what they meant to the culture of the community. My grandfather and uncle ran a forklift supply company that serviced these factories. I worked for them and got familiar with the industrial design process. I started painting using the materials that were around me at the supply company — hardwood, plywood, wood coating and salvaged material. Once I started working with salvaged materials, that was it.

Sustainability isn’t just about wind energy and solar power. It includes sourcing things in a more local way, using domestic products. A huge part of the LEED philosophy is showing the benefits that accrue when American manufacturing uses materials that are locally sourced.

The idea we have with Patterns of Meaning revolves around finding what works from the past, applying new innovation to it and bringing those ideas forward in a sustainable, adaptive way. We don’t have to discard things we’ve already learned. But people can get new ideas for their own creativity and build us all a better future.

_______________________

* Updates on the Patterns of Meaning project can be found at this Facebook page.