RACHEL MICA WEISS is one of seven Pittsburgh artists who recently received a $10,000 grant from the Investing in Professional Artists: The Pittsburgh Region Artists Program supported by the Opportunity Fund, Pittsburgh Foundation and Heinz Endowments.

It’s one more acknowledgment of how the 33-year-old sculptor and installation artist has been busily redefining the physical and aesthetic boundaries of Fiber Art not only in Pittsburgh but around the country.

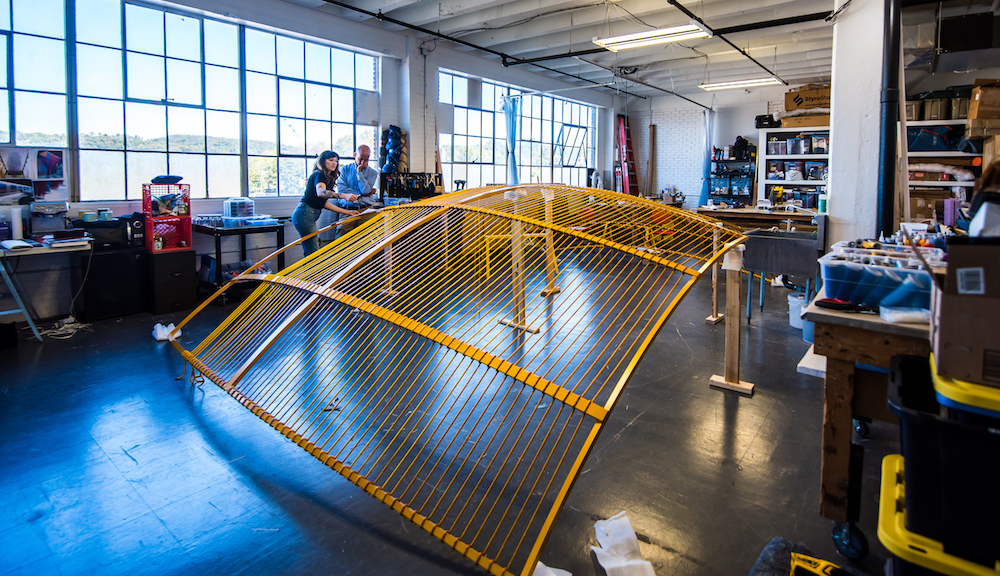

Using a mix of thread, rope, metal, wood, rocks, urethane and concrete expressed across a prismatic hand-dyed color palette, Ms. Weiss allocates her bold fusions of space and structure into artistic categories she labels Topographies, Arches, Folds, Portraits, Frameworks, Thread Installations and Unbounded.

Her art has appeared in galleries throughout the U.S. and in locations as diverse as Airbnb headquarters in Seattle, 1 Hotel Brooklyn Bridge and 4 World Trade Center in New York, Lux Art Institute in San Diego, the American Embassy in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, the Population Health Initiative at the University of Washington in collaboration with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Last Fall, Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business commissioned her Held Together installation for the building’s commons area as a provocative icebreaker to encourage conversation and contact among MBA students. In December, her 50-foot long Recto Verso was mounted above the moving walkway in Pittsburgh International Airport’s Terminal B, a shimmering homage to the Romanesque arches that grace hundreds of Pittsburgh landmarks and bridges.

Ms. Weiss recently sat with LOCALpittsburgh for an interview at her East End studio.

LEM: When did you decide you wanted to be an artist?

RMW: In 2006, I was in Senegal for my year abroad with Oberlin College, where I was pursuing a B.A. in psychology. Art had always been a hobby, but I hadn’t thought of it as a career choice. But in Senegal, I was living with artists in an artist community. I was making work all the time and I thought, “Oh, this is what I’m happy doing!” I came back to Oberlin, finished my psychology degree, lived in France for a year and then started my MFA in sculpture at San Francisco Art Institute.

In grad school I became aware that I was interested in space and in shaping space and working large. I took a weaving class at Maryland Institute of Contemporary Art and that really resonated with me. For the large-scale work I do, I learned to build a custom loom out of two-by-fours, because you can’t weave rope on a standard floor loom. I started making huge enclosures out of the woven fiber, turning it from cloth that encloses the body — housing the body on a small scale — into housing the body on a really large scale.

Weaving is a magical process; you’ve got this one-dimensional material and it takes so long to thread it through the loom, hundreds of work threads, then weeks later you finally get to sit down at the loom and weave and watch this one-dimensional material turn into a two-dimensional plane. There’s an intense gratification in that process.

LEM: What is your mindset when you contemplate creating a new work?

RMW: When I have complete control over the process, and there’s not a commissioning body or a space that dictates the work, it’s a process of play. I think about how those more metaphysical concepts translate. For example, in the Folds series, these are concrete works scaled to my body. They’re intended to be replicas of my body. They are embodiments of me, mining my own depths by forming human gestures. I form them by pushing concrete into the urethane rubber mold before it’s completely cured. At a midway point I use ratchet straps and padding and force it into its final position.

With a site-specific work or commission, it starts with a site visit and looking. Just attending to what’s around me and the architecture of the space and how does it make me feel and how does the space control my movement and others’ movement and the activity that lives within that space. I consult with architects; the work is big and heavy and needs to fill a space and feel at home in that space.

LEM: For a large work such as you’ve done for the Airbnb headqarters in Seattle or the Pittsburgh airport, how do you get a sense of what your finished piece will be?

RMW: The physical forms I build are modular, and I won’t see fully them assembled until the final installation. I may work with an architectural animator to create studio renderings; often I use photoshop and will draw 5,500 ropes on the screen rope-by-rope, copying and pasting until everything is in place. Instead of a loom with pedals, the ceiling or the walls in the space become my loom. It’s like an unfinished weaving hanging in a space; there’s no weft that ties it all together, because it’s the architectural superstructure that binds it all together. Instead of the fabric being an enclosure for our bodies, the finished work is a fabric that encloses our bodies on a large, communal scale.

LEM: How do you make your color choices for a site-specific piece?

RMW: A lot of it is about how the light interacts with the piece in a particular space. For example, saffron-gold has a glowing quality and appears as an intrinsic force of light; a darker red tends to swallow the light and doesn’t have the same luminescence. The color helps evoke a sense of place, a portal you can step through into another landscape. The work invites you into another space, yet also denies you that entrance.

I found the airport commission very exciting because it’s public art in the truest sense. People from all over the world encounter it every day, and everyone is going to have wildly different reactions. Art should speak to a wide variety of people and not just be a commodity. What I love about the airport space are the arches in the ceiling. The piece I created was mathematically based on the architecture of that space and translated into a three-dimensional object. It was unique for me, pushing into new territory.

LEM: You have a series titled “Portraits”, but it’s a very unique concept from what most people would think about traditional portraiture.

RMW: I use rocks and rope and wood frames. The rocks become stand-ins for the human body. Each rock has a set of features, the way our faces do. They’re pushing and straining against a tight mask of threads held by a frame enclosing elements struggling against a barrier, the way you might struggle to move when you feel you’re fixed, trying to capture that space of push and pull that goes on in our lives.

I’m interested in the ways humans try to enclose and shape and modify the landscape. It’s about working through these larger-scale tensions within our minds, or warring forces of nature versus humanity, and trying to tackle them in all of these dfferent media and processes.

LEM: How much of your early interest in psychology has influenced your art?

RMW: There is more of a parallel between the two discplines than you might think. I’m interested in how people work in their internal space. As an artist you spend a lot of time working alone working through your own psyche. A lot of my work is about giving form to psychological barriers and limitations and stories we tell ourselves about “you can’t do this” or “you’re not good enough” and breaking through those perceived barriers and realizing they’re perceived. All the pieces I do are caught between fluidity and rigidity, or porosity and opacity — barriers that both fluid and fixed.

LEM: Do you see your work as part of a “movement” in contemporary fiber arts?

RMW: The concept of fiber arts itself is really changing. There are many artists who use traditional methods and craft materials in a fine art context. And there is nostalgia for the tactile and the real with a new notion to explore the idea of textiles in space. The contemporary art world is seeing a resurgence of craft even as there’s a push into AI [artificial intelligence] and new technologies. I think the two trends are related, and tradition and innovation are the languages that we speak in right now in fiber arts.

LEM: What sort of art do you envision when you don’t have deadlines?

RMW: First you have to re-find the space in your mind for play, to cultivate the time to create new things. It’s totally scary because you don’t have a firm guide for a finished product. You just have to imagine and then work. As artists, our job is to look and to process the world around us and recontextualize it, so we can present it to others. Space moves me and speaks to me. I’m an introspective person and spend a lot of time looking inward, but I know the psychological experiences I have are universal and generalizable. I try to speak to the human condition and give it form on a very basic level.

LEM: Putting an abstract idea into physical reality is certainly a challenge.

RMW: There’s a great quote from the composer John Cage about the creative process: “When you start working, everybody is in your studio — the past, your friends, enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas — all are there. But as you continue painting, they start leaving, one by one, and you are left completely alone. Then, if you are lucky, even you leave.”

I never thought I would be a weaver. I never thought I would have the patience. Then it became a medium that spoke to me quite a bit. You get into modes of working. For every successful work, there are ten pieces that aren’t. The work can be insanely repetitive, but there is a meditative, almost numbing, element to the process where you lose yourself in the work. There’s even a sonic element to it when you create a rhythm, create beats in your mind. When you get lost in that, that’s magical. # # #

For more information see www.rachelmicaweiss.com.