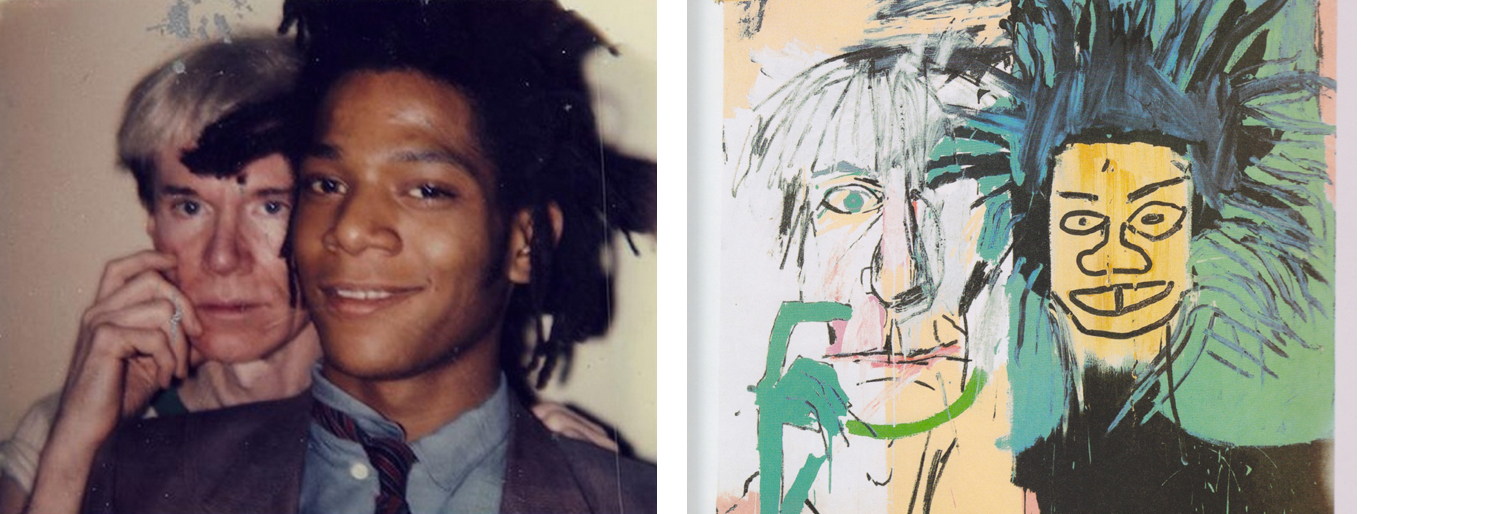

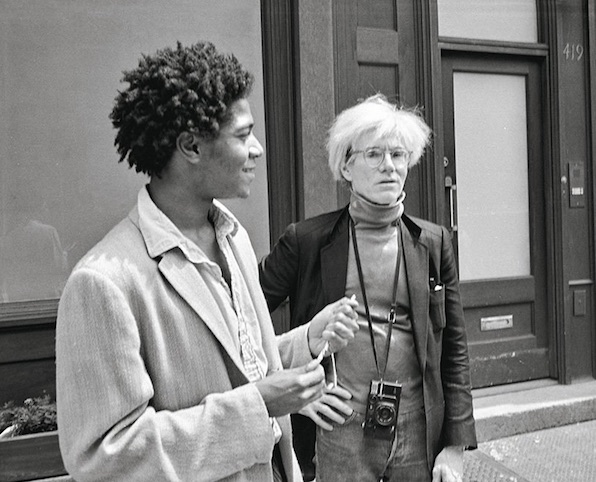

“It was like some crazy art-world marriage, and they were the odd couple.”

— Victor Bockris, Warhol: The Biography

* * * * *

REMEMBER WHEN Van Gogh and Salvador Dali hung out on the French Riviera and painted their historic series of melting sunflower clocks?

Or how Picasso’s blue period got super-jazzed after he helped Gainsborough mix oils for the Blue Boy?

Or the genius of Macy’s “Girls with Pearls” jewelry collection designed by Vermeer and Pittsburgh’s own Mary Cassatt?

Those fantasy-league collaborations between legendary artists never happened; but during a serendipitous five years in New York City, two of the most innovative artists of the late 20th century found enough time to combine talents and create exciting new, genre-busting work still influencing today’s art milieu.

Warhol and Basquiat in Focus: Works from the Permanent Collection runs from June 7-Sept. 20 at the Andy Warhol Museum and details the historic collaboration of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol from 1982-86.

Featured are photographs, paintings, sculptures and an intriguing array of archival material found in Warhol’s studio after his untimely death in 1987 (followed by Basquiat’s abrupt passing 18 months later).

For exhibit curator Jessica Beck, the collaboration was grounded by the pair’s initial experiences as art rebels and societal outsiders.

“Warhol saw a lot of his younger self in Basquiat,” she says. “Both had a hunger for being in the center of things. Not just getting gallery attention for their art but being connected to the social scene and what that mirrored in society at large.”

A quick glance at the 1980s’ work of Basquiat and Warhol suggests two striking parallels with our emerging 2020s — plague and police violence.

The explosive rise of AIDS sparked the kind of widespread fear and social backlash seen in today’s COVID-19 pandemic. Death imagery had marked Warhol’s painting for years; after his romantic partner Jon Gould died of AIDS in 1985, mortality motifs increasingly appeared in paintings like Sixty Last Suppers series and Six Self Portraits.

Concurrently, Basquiat’s aesthetic was dramatically affected by another type of loss: the 1983 fatal beating of 25-year-old black artist Michael Stewart by New York City police after his arrest for tagging a subway wall. Basquiat painted a powerful tribute on the studio wall of artist Keith Haring, The Death of Michael Stewart; a former NYC graffitist himself, Basquiat was often quoted as reflecting, “It could have been me.”

Warhol was also moved by the tragedy and created a 1983 collage painting incorporating newspaper headlines on Stewart’s death, one of his few overtly political art statements.

“Basquiat helped Warhol better understand what it was like to be a black person in America,” Beck believes. “The work they create is marked by an ongoing exchange Warhol and Basquiat were having about these moments.”

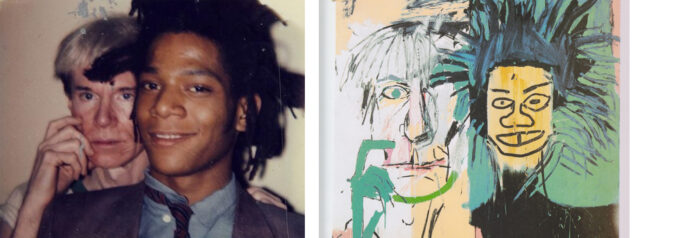

The pair’s work process indicates an undeniable bond of trust, she observes. Warhol would do an underpainting (an initial foundation with defining contrast and tonal values); Basquiat would follow with an overpainting — essentially, an “art jam” adding to Warhol’s original concept the same way a musician records over tracks laid down by other players at an earlier session.

“Even though Warhol was well-established, this relationship was not master-pupil,” Beck notes. “It was a standing of equals with mutual admiration and respect. After Basquiat’s art dealer Bruno Bischofberger arranges their first formal meeting, Basquiat and Warhol start spending time together, working together, attending openings together, writing each other. Getting to know each other as people.”

A more subliminal psychological strand can be traced via their early spiritual influences, she asserts. Both Basquiat and Warhol had strong Catholic upbringings, and both utilized religious iconography in their individual paintings.

And both artists had an affinity for wielding language as an emphatic part of their palette. “With Basquiat, Warhol is once again using advertising language, but now it’s different. There’s a new freedom, more personal references, more political references. He’s painting by hand again, which Basquiat encouraged him to do. At times, it’s a conversation that’s almost poetic.”

The conversation was certainly influenced by the language of their immediate everyday environment.

“Warhol was never an artist working in a bubble devoid of outside noise or outside media,” says Beck. “He was always engaged with the contemporary moment. Basquiat was part of the developing 1980s’ hip-hop scene in New York, and those influences from his early street artist work are very much a part of what he and Warhol created.

“What they produced in the mid-1980s still feels very contemporary. This exhibit offers a closer look at the energy and inspiration that made that possible.”

________________________

Warhol and Basquiat in Focus: Works from the Permanent Collection, June 7-Sept. 20 at the Andy Warhol Museum, 117 Sandusky St. Pittsburgh. (412) 237-8300.

Digital talks with Jessica Beck and authors Franklin Sirmans and Michael Hermann are available here.