On a second story porch of a newly bought property in Braddock, artist Jason LaCroix and I stand on small piles of chipped lead paint, holding rather dainty cups half-filled with good coffee. The house is across the street from the home that LaCroix shares with his wife, Hannah Reiff, also an artist. LaCroix bought the house from a neighbor to house his artwork as well as function as a heated studio during winter months. With the rising rents of Pittsburgh art studios, the modestly priced property will pay for itself in no time.

In the distance, the smokestacks of the Edgar Thomson steel mill emit nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compounds, coarse and fine particulates, sulfur oxides, and carbon monoxide. It’s a beautiful sight, and while the air quality is a million times better than the 1980s, when certain trees could not be convinced to produce leaves, the neighborhood lives among this invisible threat.

LaCroix tells me about Merrion Oil & Gas Corp.’s recent plans to build a well drilling pad between Braddock Avenue and Turtle Creek to frack within a 10-acre plot of land from U.S. Steel and Union Railroad Co. LLC. While no portion of the profits would filter back to LaCroix and Reiff, fracking activity would occur in the valley directly behind their home. (Both are founding members of the anti-fracking North Braddock Residents For Our Future group.) Already steel dust periodically coats the vegetables in their impressive garden. Fracking particulate matter would add an additional chemical layer.

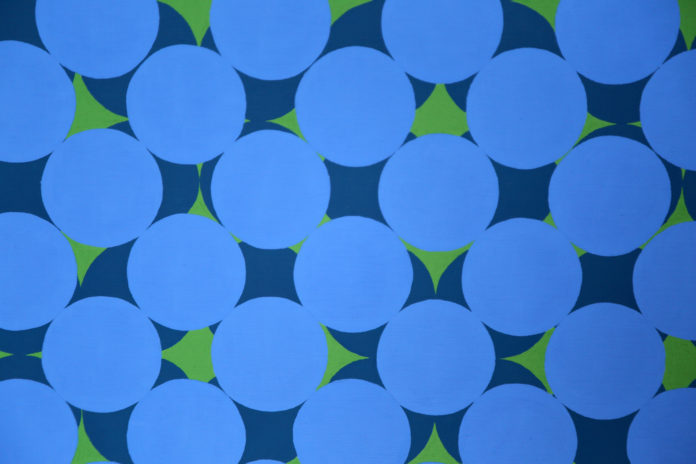

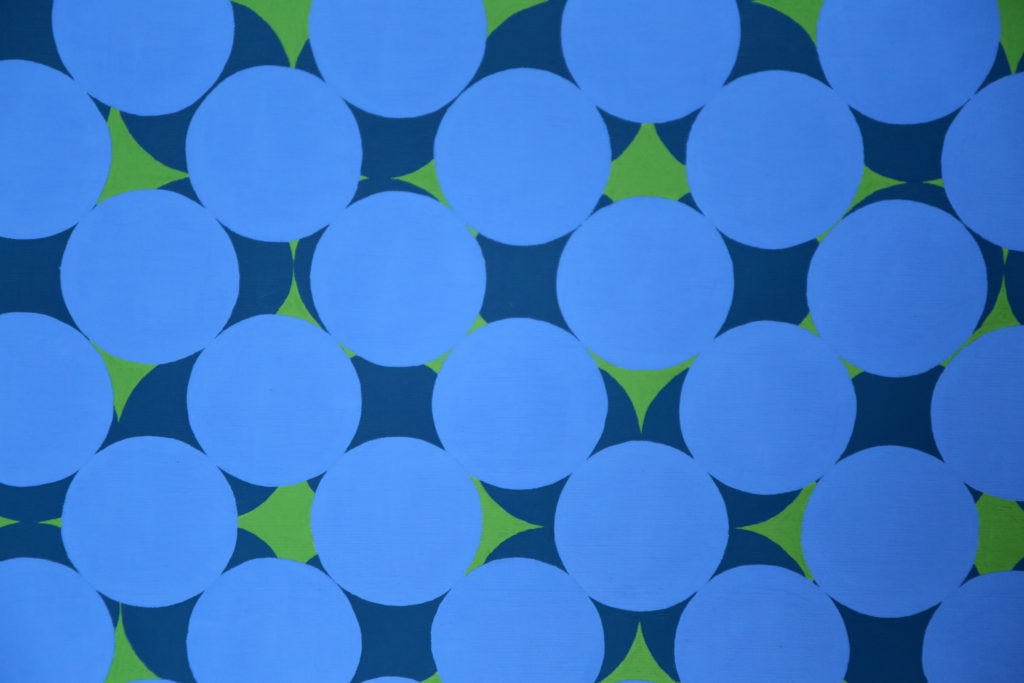

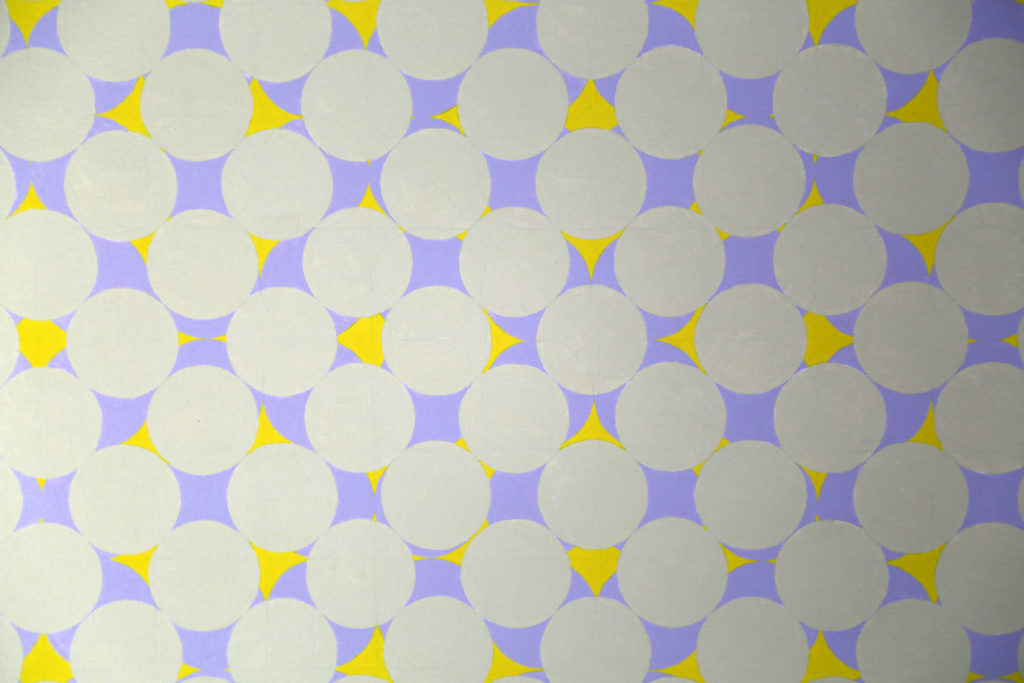

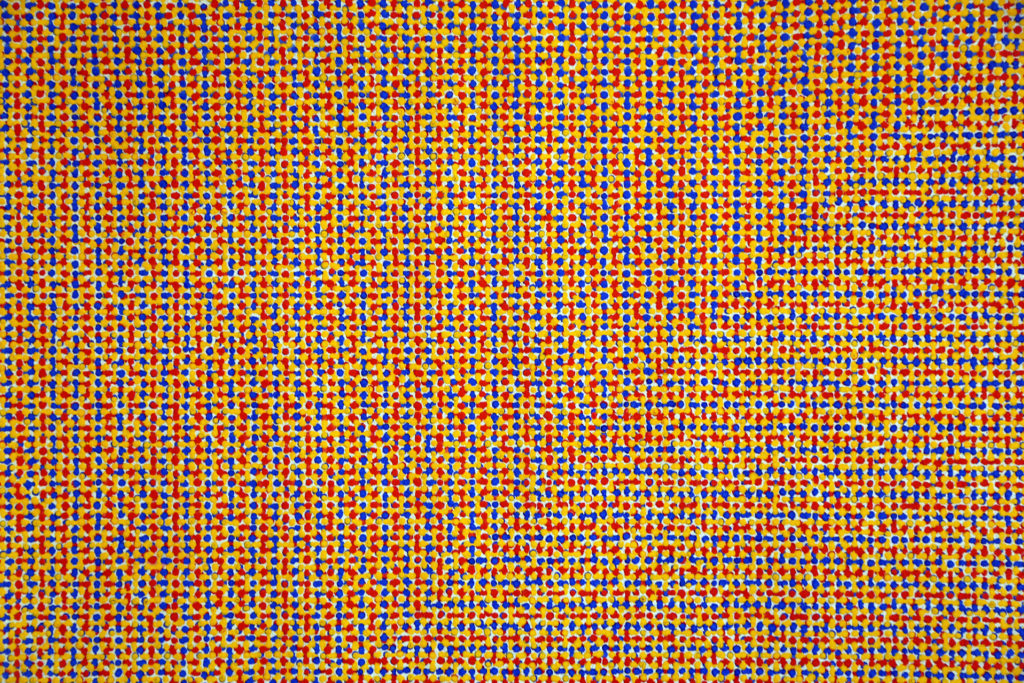

It is against this backdrop that LaCroix shows me a series of recent paintings–intricately painted arrangements of dots, each painting utilizing three colors. Each work is painted with a precision that I’m completely envious of.

David Bernabo: Do you paint these freehand?

Jason LaCroix: Yes. It’s really important that there isn’t an actual dimension. Part of the idea is collapsing the space, compressing space. I always find that a masked edge looks like a sticker. I feel like the moment there is a ridge, you can see the order of the process. Whereas, in my process, I draw my lines and then paint the edges [of the different colors] back and forth so that there is no dimension to it. How I paint is stupid. I paint the deep space. So, on this painting, [pointing to the blue painting above] I start with the blue, go back with this dark blue, and then add the green. The idea is to merge a foreground with a background.

DB: Yeah, it looks very flat.

JL: I love the look of screenprints. I’ve always been attracted to flatness, so I get into trouble in wanting to make oil paint dry like it’s screen printing ink. You end up mixing so much turpentine that you can compromise the binder, the oil, so that you can actually wipe the powder pigment off, because there isn’t enough oil to create an oil film.

DB: Why paint if you can achieve a similar, easier result with a screenprint?

JL: It might not be a good enough excuse, but I love oil paint. I love the way it smells. You have some forgiveness as far as drying times. Because I have to wait for [paint] drying times, I have a chance to pause and take in what I’ve done instead of jumping to the next decision. Another reason that I’m not just making a bunch of screens and screen printing is because I have a flat file of prints and works on paper. [That medium] is great for searching for ideas and playing around, but the printed edition idea, I just get stuck with a whole lot of material that I tote from house to house or apartment to apartment.

I just want to make paintings. I had taken a leave of absence from this kind of work. So, I feel like I’m playing catch up.

DB: What caused the leave of absence?

JL: I was doing more representational work for the last ten years. I was doing this [dot work] from 2005 to 2008, and right around when I left Boston, I decided to abandon this body of work. I had a pretty bad experience at a gallery. But I was getting into shows, finally, getting a bit of recognition, and it freaked me out. I hadn’t even turned thirty, and I thought that the dot and this whole construct–I wondered if it was a crutch. I started to question myself–you’re too young, you haven’t tried enough things to commit to this idea, you’re too committed. I was so excited with the ideas that were happening, because I was wanted so badly to have a reason to paint in a room and not paint a picture of a room. I felt like I had been waiting for some motivation to work from head or my imagination. And I was really happy when I found this body of work. This [dot-based] work was generating ideas. Each time I made something, I could see where it could have gone one direction or another, so I got excited for the next one. It kept me going for hours and hours on end.

I really love perceptual painting. It’s absorbing. I want to keep feeding it. But in 2008, I thought it was all bullshit. It started to feel like I was starting to participate in the art world, and I questioned that. It’s like a strategy-type game, where it’s like I’m going to totally abandon something that’s been feeding me, because I want to demonstrate that I have the control to just say, “done.” And it caused a rift with some of friends that said, “You have a lot of fruit to harvest here. There’s enough landscape painters in the world.” And it’s comments like that that caused me to think, “Well, fuck you. I’m going to paint landscapes and do exactly what you don’t want me to do.”

It was a decision that I made, but it’s been about 10 years of carrying these ideas around, this guilty love affair that I had with these dots and grids. But there came a point where I gave myself permission to do one again. My friend, Brandon Boan, gave me this blue canvas, and I immediately wanted to fill it up with white dots and give it back to him.

LaCroix’s paintings could be accused of being accessible, pleasing colors and recognizable shapes. It’s not a bad thing. But there is something much deeper to LaCroix’s craft.

JL: I’m not trying to make paintings that are appealing palette-wise or are interesting designs. I want my color decisions to not be based on “well, that looks good,” but rather is it working, is it doing something, is it necessary. [Pointing at three paintings on the ground, photo below] I don’t necessarily think these paintings work. Part of the goal with these paintings was trying to take situations in an observed world and bring them into my painting. This yellow-ish painting is looking at the color relationships in my studio. The blue painting is looking at cornflowers in my garden. The orange painting was inspired by the center spot of a just-opened echinacea, because it is a cluster of orange tubes with red ends against a dark green cone in the middle. These paintings are inspired by those colors as a starting point, but as I put paint down, I fought with the idea that even though the colors have a base in nature, the colors do something else [once on the canvas].

Here the conversation turns nuanced. LaCroix discusses how he can match the colors found in nature–replicate the original inspiration–and paint them on a test board of wood, but the context of how those colors interact in his painted grid pattern is different than the context of those colors in nature or on the test board. The final context of the painting and the interaction between the colors can’t be known until the painting is made. The positioning of one color next to another alters the perception of that color because the relationship changes and a viewer’s perception of what the color is also changes. In this way, the painting stands alone as a unique experience, providing its own reason for existing.

JL: I would like to get away from the fact that the pattern is determined by the geometry. I’m starting to get uncomfortable with geometric aspect of these paintings.

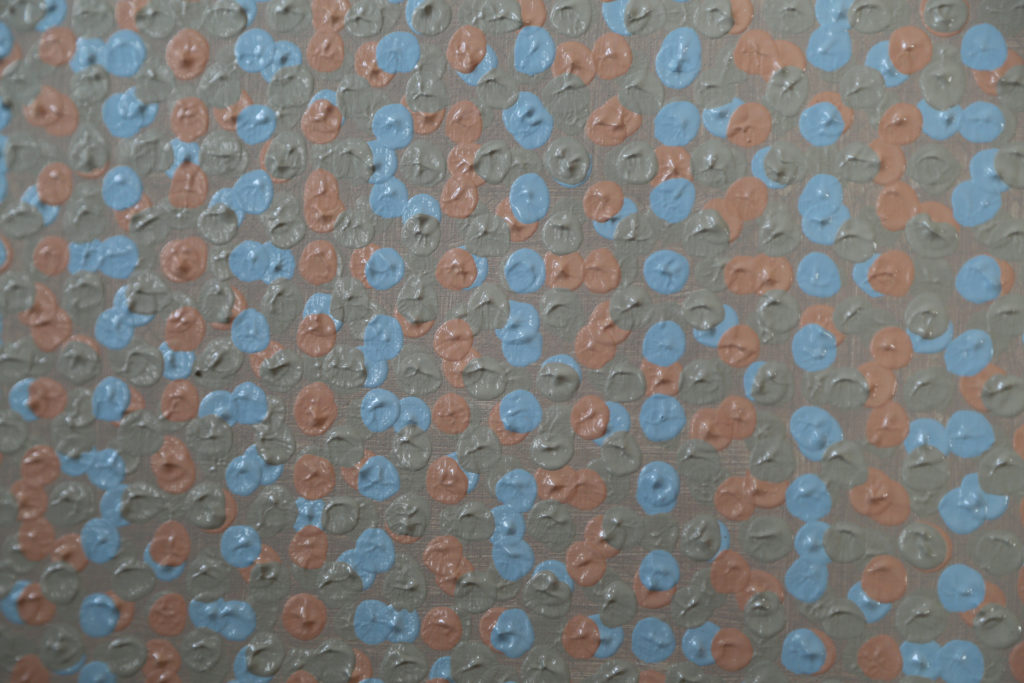

I was studying in Italy and this gentleman had this idea to make a painting of waltz steps. You know, like if you are learning a dance, you follow the footsteps. So, he was painting the image of shoe shapes onto the canvas. And I thought, why don’t you just step into paint and step on your canvas. You’re illustrating steps when you could make the steps. That idea of putting a layer between it–[returning to his paintings] these circles, these dots represents marks. So, I’m getting back to the idea that I need to relinquish control and order and clarity, that these dots should probably be marks, just single brush marks. Which in retrospective, going back 15 years, is how it started.

DB: Is a mark less formal than the dots, though? A mark is still a decision and still an action.

JL: Well, let me show you. [Points out the loose dot nature of the below painting.]

DB: It’s interesting, going back to what we first discussed–compressing the paint–here, you can see the process. You can see the order of operations.

JL: Right, part of the game is that, yes, I can see that this mark is on top of that orange mark. What I want to question is relation–if this tan mark is on top that orange mark, then how is that orange mark on top of that tan mark.

DB: Yeah, what are the rules of this game?

JL: The idea of a contradiction caused by systems. It’s the result of a repeating pattern on a grid with another shifted, diagonal grid placed on top of it.

These paintings are very labor intensive and all absorbing. Sometimes I wonder if the outcome really is as important as the process. The paintings suck me in for an extended period of time, and I get my mind off some other stuff. It’s meditative. You can’t put a value on that.

Let me show you something downstairs.

We walk downstairs. On an easel, there is a rectangular piece of canvas filled with thousands and thousands of dots.

JL: This thing was kind of a mistake from the beginning, but I just kept going. At so many points, I thought…you thought you were going to be done with this in a week. A few months later, now you’ve gotten this far, you gotta keep going. So then, that’s when I don’t know what my art is really about. Diligence? Patience?

DB: And how do you price three months of work?

JL: Yeah, I have no idea! That part sucks. Once someone sees it, they ask how much is it. That’s not the point. I’m trying to get you to see something. Let’s try to suspend the whole market, the commodity system. Let’s just not go there. It’s about the journey.

If I said two grand. Someone would [write it off]. Well,how much do you make at your job? $10/hr? $2,000 doesn’t even get me $10/hr. for this painting. It doesn’t make sense to make art.

I was working in my studio when I had some house painters over. I felt bad the whole time, thinking I could have been painting my house, but I’d rather be in my studio painting these pictures. But I paid someone $4,000 to paint my house. It took them a week to paint my house, and I was still on one layer of the dots that I was working on in my studio. I was thinking, could I get $4,000 for this painting, based on the time that I spent making it. It’s frustrating only if you’re hung up on needing to make a living from art. That’s why I make money from a restaurant. I don’t have to undervalue myself or sweat it or be consumed by that [money-making] idea.