Part two of our three-part series on local band The Garment District delves into Jennifer Baron’s nostalgic memories and childhood musings that have melded together to form the mélange of influences present in the band’s music and visual accompaniments. In this extensive interview Baron discusses everything from band posters that hung in her family home to the influence of old cartoon sound bits and the way all of these small components of sound and visuals impact her creative process and the music produced by The Garment District.

Julianna: What objects have made creative impacts on you? Are their certain belongings or heirlooms you treasure?

Jennifer:The ocean, nature, art, film, poetry, design, architecture, dreams, travel, memories, my dog. I guess if you were to answer that question by walking through my house, pursuing my music collection, snooping around my walls and shelves, you would say music, design, film and art from the 1960s and 1970s from different places around the world. I gravitate toward collecting objects I am inspired by and drawn to and these include: vintage Pyrex and dishware; enamel flower pins, vinyl records, analog instruments, paint-by-numbers, polyester dresses, textiles, motel postcards . . .

My husband has an astounding vinyl collection which has merged with mine, and we share a ton of musical interests from Freakbeat, free jazz, and library music, to British psych, Jamaican music, and early electronic sounds, so we always have our 1970s Marantz turntable going. Moving into my first house, I have been able to assemble my instruments and create a space that is conducive to making and listening to music, unwinding and escaping into the process in a more immersive, less nomadic way.

I would definitely describe myself as someone who is very aware of and impacted by my surroundings, and this can be both uplifting and detrimental, both expansive and limiting at times. Nature, weather, space, architecture, sounds, visuals—I feel that I am very tapped into and observant of these elements and they can often shape or seep into my psyche and creative process.

Julianna: Do you have any early memories from your adolescence that you believe have affected your music?

Jennifer: Growing up, our house was filled with LPs, cassettes, and CDs. Vinyl records were literally some of our first toys. Our cars always had tape decks and 8-track players for our many road trips… Some of my first pre-verbal memories are of staring at fantastical and evocative album covers, such as The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, Beatles records, the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Axis: Bold As Love, Cream’s Disraeli Gears, Jefferson Airline’s Surrealistic Pillow, Donovan’s A Gift from a Flower to a Garden, Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks, and many others.

My mom was a high school English teacher… She taught a course called “Poetry and Rock Lyrics,” and I loved helping her write song lyrics on index cards for lessons and classroom decorations. We did not grow up with religion, so I always joke that Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, and Neil Young was the holy trinity in our house. My parents have lyrics to Dylan’s “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” from Blonde on Blonde written in calligraphy and framed on their wall, so the music of the 1960s and 1970s is in my DNA.

We also had tons of children’s music on LP and a Fisher Price turntable with thick plastic “records” that had grooves. I remember the small red and yellow children’s 45s with songs like The Muffin Man, which must have fueled my interest in offbeat folk music and melodies. We listened incessantly to Free To Be … You And Me and Puff, the Magic Dragon. My brother and I would act out our own radio shows, recording them onto Maxell tapes. We spent hours pouring through my parents’ old copies of Mad Magazine and Rolling Stone and staring at album artwork while listening—which is so much more of a direct way to hear music than the way most people experience sound today.

When I was little, I read a ton, both alone and with my mom. One children’s book that has stuck with me as an adult is Arm in Arm by Remy Charlip, who I named one of my songs after. He was an American artist and educator [whose] book was a source of great imaginative experiences… Arm in Arm is filled with visual, kinetic, and freeform poetry [as well as] clever word-play; [it’s] concrete poetry that forms shapes and pictures. I think [these] early influences have helped to shape my sense of pattern, rhythm, phrasing and texture in music.

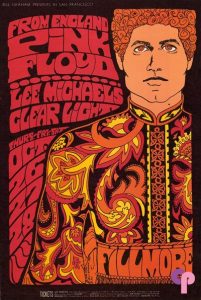

Growing up we also had some mind-blowing concert posters and postcards by legendary Fillmore West artist Bonnie MacLean hanging in our house. One in particular, for a Pink Floyd show, I found to be hypnotic. As a kid, I think I associated the male figure with my dad because he had the same thick curly hair as the figure on the poster… Seeing her posters as a child definitely shaped my psyche and interest in design. My dad also created drawings and paintings that were around our house and my mom sewed our curtains and clothing (all inspiration for my song “Secondhand Sunburn”)—some I still have today.

Julianna: A lot of your music videos rely heavily on what appears to be recovered and archival video footage. Why did you choose to go this route aesthetically?

Jennifer: I am definitely drawn to a visual aesthetic that combines the creation of new imagery with repurposing existing imagery. Sometimes answering the “why” is a highly personal thought process that is difficult to express using language. I do also love processes of fragmentation, collage, and layering that lend themselves to using found, archival, and fair use footage.

While I am not a filmmaker or videographer, I love both art forms, and I think very carefully about artists I want to work with. My music videos range from works that were made using footage my step-father shot on my iPhone while I served as a creative director (Bird Or Bat), to ongoing collaborations with multimedia artists, to filmmakers using my music as the foundation for their own original video works, to my culling obsessively through found footage (Only Air and The Parlance) and working with a video editor.

I obsessively take photographs, and I hope to create music that has visual content and creates visual interior realms. I do think that there is a strong connection between the two and that there is a fluid synergy between the music I write, my photography, and my music videos.

For me, making images with all sorts of cameras has always been concurrent with being in bands and writing my own music so I do see a meshing of the two in my artistic process. I love the way photography can be fractured to document a moment, an experience, or a fragment, but can also open up into new worlds and patterns of thought and expression… I think music can also accomplish this.

Julianna: Garment District’s music seems to be simultaneously upbeat, melancholy, and nostalgiac. How would you describe the kind of music you produce and who/what would you name as your primary influences?

Jennifer:Some aspects of writing and recording music are highly personal and private, almost a process akin to alchemy. You can’t always translate the process to a specific language. It’s also a slow-moving process that reveals itself over time.

I trust listeners to describe my music, based on your personal experiences with it, such as:

Your music makes me feel like I am 10 years old, stayed at home sick on a school day watching Inside/Out on PBS. The record gives me the oddest combination of wistful wanting to go back to some far away virginal loneliness and a more blissful almost mushroom-tripping elfin magic thing.

Atmospheric and evocative. I feel like I am tuned into a time-travelling satellite when I hear this band. Are they a super-advanced band from the 1950s? Or are they a vintage/retro computer simulation from 2070? Or both?

Reviewing our recent concert at Cattivo, Pop Press International described The Garment District as: “At once approaching Kraut-rock frenetics, the band would swerve into ’60s California Spector-rock and then AM Gold pop before careening back into terrestrial psychedelia”—which I really think fits.

When I write and record music, I don’t concretely or consciously think about influences. I have always thought of it more in terms of inspiration. I try to focus on listening carefully to what is in my head, then interpret and give that form, via my collection of analog instruments, a sense of melody, possibly lyrics, and also allowing what I am playing to have the chance to evolve into something new or unexpected.

Courtesy of Jennifer Baron

I [experiment with] different analog instruments and figure out how they can work together to communicate a song or piece of music that starts inside my head; allowing the instruments, melodies, patterns, and textures to create an entire sonic universe that transcends the limitations or baggage or preconceived notions of language. Almost like a pre-verbal phase or a dream state. Lifting the limitation imposed by a narrative or word allows the music to become almost spatial.

My way of writing is very naturally melody-based, and the way I approach my music is how I hear everything in my head; it starts to unfold and evolve as I am writing and recording, creating a demo, or experimenting with different instruments that are in many rooms of my house. That process is highly personal and intuitive for me. What the song or composition requires and calls for is what dictates how I proceed. I think very carefully about every note, melody, pattern, instrument, lyric, layer, etc. A lot of thought and care goes into my process, even if the end result is more freeform or experimental.

I have always been interested in the intersection of orchestrated pristine pop music and the vibe and feel of more ambient experimental stuff. I love that music exists at a particular point in time, with a beginning and an end. It’s temporal and also temporary, and can take you to another place or time, or to your own past, or memory of the past, or be wrapped up in projections of the self, and can be a form of escapism.

Unfortunately, most music is our digital culture is relegated to background music. I love ambient sounds, so I even get offended at my neighborhood pool when they blast a classic rock station because I want to hear the ambient sounds of kids playing, water splashing, birds, the wind, cars whizzing by, the lifeguard’s whistle. I often take an inventory of sounds around me, making field recordings in my yard, around Pittsburgh, and on trips for possible use in future music. I find it to be troubling that we clog up hearing, noticing, observing and listening—so much so that we can’t experience things fully without distractions, mediation, and multi-tasking—and I think it’s reached an epidemic level. I honestly feel that music can free us from this trap.

Films (I am pretty addicted to watching documentaries)—as much as music—favorites such as Picnic at Hanging Rock, The Swimmer, Bunny Lake Is Missing, The Wicker Man, Grey Gardens, Seconds, obscure horror films—and experimental cinema of the 1960s-1970s—can often trigger something that inspires me to make music. I think more in terms of inspiration as an energy force, rather than a traceable or literal influence. Things seep into your subconscious and may end up making their way into your artistic voice in unrecognizable… ways.

I am endlessly in awe and of and uplifted by a massive range of music—including 1950s-1970s psychedelia, folk, pop, garage, freakbeat; 1950s—1970s rocksteady, ska and dub; early electronic music; free jazz; 1980s NYC hip hop; 1970s-1980s pop and new wave from Scotland, New Zealand and Australia; as well as film soundtracks and TV and cartoon themes. I can be just as inspired by a brief interstitial composed by Joe Raposo for Sesame Street or a 1960s/1970s horror film soundtrack, as I can by some of my favorite music.

I love to discover soundtracks from films and TV shows from the 1960’s and 70’s that are not well documented. Such as hearing a part of a musical piece or interstitial music that moves the action along, or suggests a narrative, character trait, mood, time or setting—I love that music has that kind of presence. My husband recently gave me a fantastic book, Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music, by Rob Young, which delves into so much of the music, culture, landscape, history, and politics that inspires me from the late 1960s.

Taking listeners on an emotional and aural journey throughout an album is something I work hard towards as a concept for the music. I love the concept of an album as a complete experience curated by the maker, from start to finish—like a trip into a fantasy world, or in and out of subconscious states, which is what I hope it can do for listeners. This is how so many significant old albums of my childhood are represented in my mind. I always hope that my music can provide a kind of escape from all of the multitasking, fragmented attention-deficit realities of daily life. I love the idea of creating a musical itinerary for people to listen to; like, that they have to sit still and focus on to truly absorb and internalize. That way, the music can go in a variety of directions once it is occupying physical space and people’s internal consciousness. Likewise, I don’t just have one way of writing and creating music.

The Garment District’s releases can be found at Mind Cure Records, Sound Cat Records, and The Attic Records.

Music and videos from The Garment District.