Photos by Tyler Polk

Allegheny County Air Has Improved, But It Is Still Mired In Major Problems

Since moving to Natrona Heights, Donna Frederick, says she has had to wash her car at least three times a week to remove dust since moving across the street from one of the region’s worst polluters.

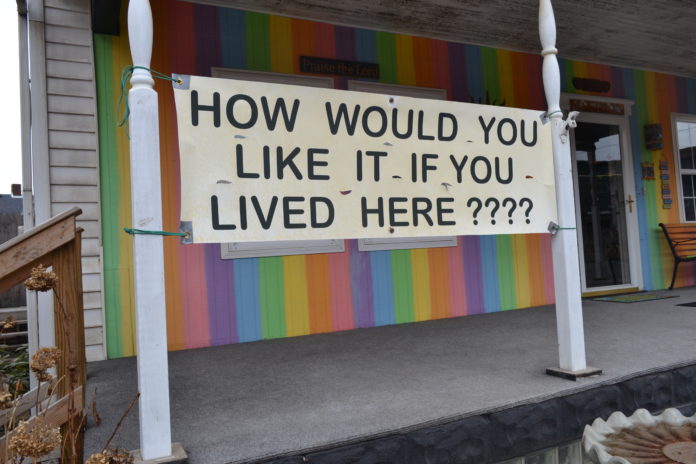

Marti Blake, a resident of Springdale says coal dust comes into her house from the toxic Cheswick Generating Station even with her windows closed.

These two people all live next to facilities listed in the Toxic 10, a list of the ten most toxic air polluters in Allegheny County. The periodic list shows while air is better in this region after the closure of many steel mills and other polluters, it remains among the worst in America.

The first Toxic 10 list was released in 2015 by PennEnvironment and it used information from 2013 and 2014 to compile the rankings. The second toxic 10 report was released in February, using data from 2016 to report on the problem. You can find the latest report at toxicten.org.

“The reaction was really strong, but the Allegheny County Health Department and the facilities were not so much a fan of the report,” said Zachary Barber, PennEnvironment’s Western Pennsylvania Field Organizer.

“There’s a lot of groups doing air quality work in Pittsburgh, but this was the first time someone provided a roadmap what the pollution landscape looks like”.

“We appreciate PennEnvironment’s commentary regarding air quality in our county. It is important to note that some releases of toxins are allowed under EPA standards, and they are not considered violations,” said Karen Hacker, Director of the Allegheny County Health Department, in a February statement.

Self-Reported Data

The Toxic 10 is built using databases from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These databases use self-reported data on what toxins were released, how much in pure tonnage, and how bad a chemical is.

“We looked at how much they put out multiplied by how bad it is to get the toxicity score”, said Barber. “We looked through each facility for everything they put out and added all together to get the overall score for the facility.”

One in three of the 1.2 million people living in Allegheny County live within three miles of the facilities listed in the 2015 report and Barber says that there are similar numbers for the newest Toxic 10 report.

“They see, smell, and taste what’s in the air and understand the entire range of issues, from the quality of living and health to property impacts,” said Barber.

Pollution in Natrona Heights

When Donna Frederick of Natrona Heights bought her house in 2007, she figured she would rather live next to the noise of the steel mill than next to drug dealers she had lived close to in the past.

“Through the years I found out that, it would be better to live next to drug dealers, than live next to ATI,” she said.

Frederick has lived in Natrona Heights for ten years, right across the street of ATI Flat Rolled Products, also known as Allegheny Ludlum. The facility was ranked number two on the latest Toxic 10 report.

The Toxic 10 report found Chromium, Cobalt, Hydrogen Flouride, Lead, Manganese, and Nickel compounds coming from the plant. These substances are on the EPA’s list of hazardous air pollutants and are suspected to cause cancer and other health effects.

“We take our responsibility to the communities in which we operate very seriously, including those in Western Pennsylvania,” said Scott Minder, a spokesperson for ATI. “We now have the best available pollution control equipment installed on our Brackenridge HRPF and melt shop facilities.”

“I’ve taken multiple pictures and videos [of the results from the facility’s emissions],” said Frederick. “I’ve had GASP (Group Against Smog and Pollution), take samples of my soil and red residue in my bird bath”.

Recently, Frederick had samples tested from her soil by ALS Environmental, the report found amounts of mercury, arsenic, barium, cadmium, chromium, and lead. These are two hazardous air pollutants according to the EPA.

“We have a swimming pool, and because of the residue getting into the filter, we have to clean that every day,” said Frederick.

Living next to the plant has left her house covered in a white ash-like residue, and the smells of rotten eggs, wires burning makes it hard for her to sit out her porch.

“It’s sad that you can’t sit on your porch and have coffee unless you want your lungs to hurt,” said Fredrick. “This area is known for rentals, so people would buy the houses not knowing [about the pollution]”.

Her neighbor, Rebecca Miller, said the smells forced her to leave her house on two occasions.

“The first time, it made me dizzy, I went shopping and came back home and I really noticed it”, said Miller. “Another time it was a burning feeling in my throat and my eyes. I smell it often, but it’s never been like those two times, but it’s still strong.”

According to the Allegheny County Title V Operating Permit Status Report, Allegheny Ludlum has never been issued a Title V permit in its history.

A Title V permit is required by major sources of pollution and certain facilities for these sources. The permits are enforced federally and can add additional requirements to facilities such as emissions fees and compliance reviews.

According to a spokesperson from the Allegheny County Health Department, the facility was in the draft permit stage and found new information about emissions they were not aware of and have made new limits since then. Currently, the Health Department is reviewing comments from a public meeting from December 19th, 2017.

Pollution in Springdale

After selling her house in the North Hills in 1990, Marti Blake had two weeks to find a house for her and her two children, then ages three and six. She moved into her house in Springdale across the street from the Cheswick Generation Station, a coal-fired power plant.

Penn Environment’s Toxic 10 list ranked the plant as the number one Industrial air polluter in Allegheny County. The report found Arsenic, Chromium, Dioxin, Hydrochloric Acid, Hydrogen Flouride, Lead, Manganese, Mercury and Nickel compounds in its emissions.

“The air surrounding NRG’s Cheswick Generation Station meets the requirements and emissions from Cheswick are far below its permit limits and is doing much better than its required to do under its current Title V Air permit,” said David Gaier, a spokesperson for NRG.

“My mother told me, Marti, you’d better get out of there or you’re going to get cancer,” said Blake. “My mother was very smart, but at the time, I had nowhere to go.”

Marti now has asthma and must take an allergy shot every four days. Four years ago she was diagnosed with Melanoma.

While there is no medical relationship known between health and the plant, according to a 2013 study from the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Allegheny County is in the top 2 percent of cancer rate in the United States.

“I had to have surgery, on my arm, and had lymph nodes removed,” said Blake. I have to go to a dermatologist to get a full body scan every six months to make sure nothing else is popping up.

Coal dust from the coal plant, comes into her home, even when the windows are closed. She cleans her house every spring and one year, it went from bright sunlight to darkness for five minutes. A man who was across the street watching her apologized for the coal dust cloud ruining her work.

“He says, that came from the plant,” said Blake. “I’m so sorry. I’ve been watching you, you’ve been working so hard all day and washing the building down, and then this happened.”

Blake has photos of the soot from her property from other instances of coal dust on her property, and pieces of the paper towel she used to clean her property.

She created her own air quality activism group for Springdale residents called Citizens Against Pollution. She would go canvassing or campaigning around the neighborhood, but the group has since disbanded.

Blake now volunteers for the Sierra Club and presented the evidence of coal dust on her property during the public hearing for the new permit for the Cheswick Generating Station in August 2016.

Residents concerned with air quality and people who work for the industrial facility presented their opinions on how the new permit should regulate emissions.

“There had to be over 100 and some people there,” said Blake.

In Part two, we will focus on the Mon Valley where a filmmaker is hoping his production will spark change in the fight for clean air and two people from Clairton who are fighting for change as well.